|

Laboratory

– Shield-Bearers

In

Sept., 2007 I had got the idea of checking whether, in ancient

armies, there had been instances, other than Ey-de-Net and Dolasilla,

of archers fighting in a team with a shield-bearer devote to their

defense. About this subject, I had proposed a first version of

this “Laboratory” where I concluded that the idea

of protecting Dolasilla by means of a shield-bearer should have

come to the King of Fanes’ mind authonomously, provided

he wasn’t aware of the Assyrians’ methods of combat.

Later on, I received two contributions, one by Alessandro Manfroi,

who, among his various capabilities, is also a skilled archer,

and one by Davide Ermacora, who prospected me the Mycaenean “warrior

duo”, which I blatantly ignored.

| As

a matter of fact, I believed that the only people of the

Ancient Age accustomed to that way of fighting were the

Assyrians. See the detail on the right, See the detail at

right, illustrating a combat team, dated about l'884 B.C.

(today at the British Museum). In this case we have two

archers and a shield-bearer, who propped up the huge structure,

probably wooden,(although John R. Edgerton,

through A. Manfroi, suggests that it might

consist of reeds, and therefore be much lighter) insisting

on the ground and providing also some protection from above.

The bearer looks to be using his left hand for the shield,

while the right one holds an edeged weapon, maybe a short

one; or it may be a second handle used to turn the big thing

around. He wears a cover cap like the archers, but his gown

is short instead of coming down to his feet, and probably

he wears an armour and shin protectors, while the archers

appear to be fighting bare-breasted. Notice the latters'

quivers, strapped across one shoulder, and the swords at

their belts, maybe in a sheath. Last, while one archer and

the shield-bearer wear their classical long beards, the

closer archer wears none. Age difference, national usage,

or just fashion?

At first I had supposed that what we can observe on the

other side of the shield could be a flame, or an explosion.

The same John R. Edgerton provided us with

the complete picture, where we can clearly see that we are

dealing with a tree, and no explosion. A further essential

detail can be acknowledged: in the upper left corner there

is another archer, presumably a foe, who is shooting arrows

from above a wall.

. |

|

|

|

The scene,

therefore, doesn’t depict an open-field battle,

but a siege. This circumstance, if it gives a better rationale

to the usage of a so scarcely mobile defensive structure,

on the other hand reduces its value as a comparison reference

with the pair Dolasilla-Ey-de-Net.

Such teams could also be composed by an archer, a shield-bearer

and a swordman; or by two people only, one archer and

the shield-bearer.

|

|

Then

we have the image of a heavy Assyrian battle-cart (by courtesy

of mr. Bede, from Sidney, Australia), with

four people aboard: two archers, and two shield-bearers.

The latters, however, use a round shield, similar to those

used by infantrymen. |

|

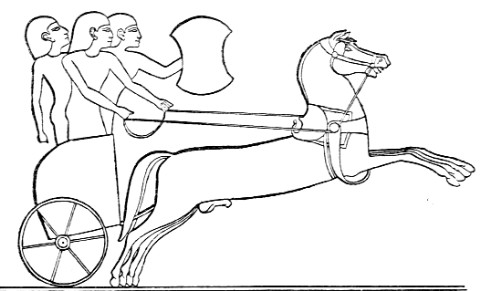

This type of

combat by small teams was not used, as far as I know,

by other populations, with the exception of the teams

mounted on chariots. What we can see at left is an egyptian

representation of a hittite chariot. We have a charioteer

an presumably a warrior, although the schematic sketch

doesn't allow to understand which weapons does he carry

along; besides, we have the shield-bearer, who makes use

however of a much smaller and nimbler object than the

colossal object of the Assyrian siege unit.

|

In the Homeric description of the war of Troy, it seems that the

chariot team was composed by two people only, the hero, who was

completely armed, and his charioteer. But the Greeks, with the

important exception I will describe later, (I might generalize

and talk of Europeans), don't seem to conceive any combat by small

teams. Heroes fight alone, and the mass all together. Archers,

when they are present, fight each by himself. It seems that archers

never were considered of relevant importance in Greek armies,

as well as in Balkan, or Italic, or Celtic ones; less so, that

any of these populations ever felt the need to assign a man to

the specific task of shielding an archer. The Macedonian phalanx

(yet to come) will later use (several) "shield-bearers"

to shelter its right side, relatively unguarded, but in a quite

different tactical situation.

Davide

Ermacora, however, indicated me the important exception

I was referring to above. It consists of the Mycaenean “warrior

duo”, composed by an archer and a heavily armed infantryman.

Unfortunately, the rich bibliography listed by Davide

is difficult to retrieve, unless one has a specialized university

library at hand. Anyway, I found something, and something was

kindly handed over to me by the same Davide.

Thence, let us see in more detail what happens in the war of Troy

itself.

In

the Iliad, only three Greek heroes are mentioned as archers: Philoctetes,

Meriones and Teucer (there are

also the Locrians [people from the so-named region

of Boeotia not from Locri Epizephiri in Calabria, which was founded

as a Locrian colony many centuries later], about whom in the XIII

chant it is said that they are “arrowing and slinging”).

Ulysses, who in the Odyssey is described as an

exceptional archer, in the Iliad appears having forgotten his

bow at home (as a matter of fact, he will find it again –

in the other poem – at the moment of slaughtering the Proci).

Philoctetes, from Magnesia, who is the lucky

owner of the bow that was Heracles’, leads a party of as

many as fifty archers, but during most of the war remains away

from the battlefield because of a wound;

Meriones, from Crete, who gains the bow contest

in the games on Patroclus’ death, in battle uses however

conventional weapons like sword and lance.

Teucer, brother of Ajax the Telamonian, from

Salamis, on the contrary uses his bow in combat, and this way

he kills several Trojans. His fighting style, that makes him of

special interest in the light of the Fanes’ legend, is that

of sheltering behind his brother’s large shield, uncovering

just to shoot, and immediately returning under cover “like

a child to his mother”. The virtual analogy with the pair

Dolasilla-Ey-de-Net is patent.

More so, Ajax’ shield covers him from chin to ankles, is

shaped “like a tower” and is large enough to shelter

his brother as well. It is composed by seven layers of oxen leather,

covered by a bronze sheet, and is so heavy that the hero –

the most powerful among all Greek warriors – hangs it to

his shoulder with a strap, and even so he must sometimes be helped

by his comrades. Again, the comparison with Ey-de-Net’s

shield, “so heavy that he was the only one who could bear

it” comes immediately to one’s mind.

Several

passages (some of them lexical also) hint at Ajax’ character

representing an archaism in the Iliad: he uses a helm with side

guards and a tower-shaped shield, no body armour and a huge lance

as his only offensive weapon. He is the only hero using that type

of weapons and that fighting style, which is not typical of the

Troy war times, but of the XVI-XV century B.C.! Therefore his

character might be built upon an archetype pertaining to epical

poems of the Mycaenean age, that is, even much older than the

standard version of the Iliad. This is prof. Alessandro

Greco’s conclusion, the top Italian scholar of

Mycaenean culture, who goes as far as defining the pair archer-hoplite

(=a heavily armed infantryman) as the “classical Mycaenean

warrior duo”. I’m expecting to be able to read more

of his writings in the next future.

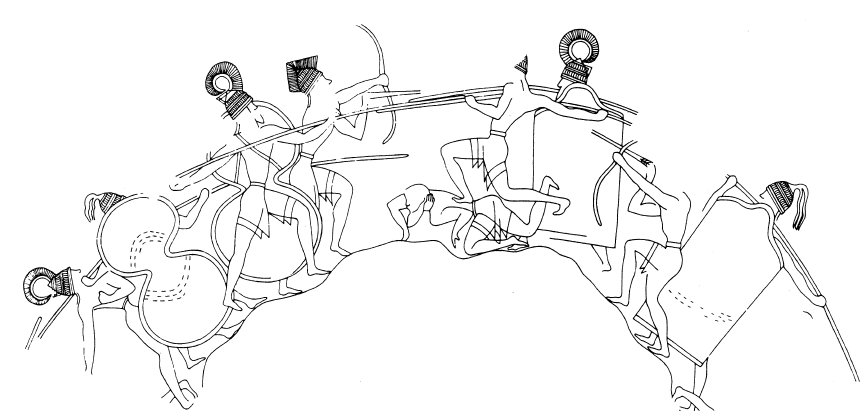

You can see in the picture here below, derived from an engraving

on a silver cup found at Mycaene in a XV-century B.C. grave (see

Bibl. 8), a fight with tower-shaped shield and lance, involving

archers. |

|

Notice that the warriors on the right side use a tower-shaped

shield and those on the left an eight-shaped one, but they all

use a lance as their single offensive weapon. Both parties fight

with no other body protection but their helms, of various types

but common to both sides, and don’t appear in “heroic

nudity”, but covered by a short gown. The third warrior

on the left clearly shows how the huge whole-sized shield was

used: it covered the warrior’s back, hanging from a shoulder

strap, so leaving both hands free to handle the lance. Obviously

the fighting style must have been peculiar to suit this type

of weaponry. Then we have the archers, one on each side, with

helms like the hoplites', but naturally bearing no shield. Their

bows show a slight double curvature, and might therefore be

of a composite type (the period might allow this).

It is finally to be noted that the fourth warrior on the right

side is deprived of both shield and bow but is armed with his

lance; he looks like jumping on a comrade’s back (to increase

the dash in handling his lance?). It might have been a peculiar

subterfuge that possibly had been used in a specific war episode,

the subject of a well-known epic narration, which the scene

engraved on the cup was depicting.

We must underline, anyway, that the pair archer-shield bearer

doesn’t appear as having been a typical structure of any

post-Mycaenean army; in the Iliad Ajax and Teucer are the only

instance, and no others are known at later times.

We are apparently allowed to propose the suggestion that those

who detailed the Fanes’ legend were acquainted, if not

with the Homeric poem, at least with the previous ones, upon

which the Iliad must have been based. At the present moment,

however, it’s too early to draw any conclusion: anyway,

this is a totally new strand to explore, that can bring to interesting

developments.

I’m enclosing here the bibliography kindly provided by

prof. Greco, through D. Ermacora

(the last title is the only one I was able to read until now):

1.A. Greco, "Aiace Telamonio e Teucro. Le tecniche

di combattimento nella Grecia Micenea dell'epoca delle tombe

a fossa [Ajax the Telamonian and Teucer. Fighting techniques

in Mycaenean Greece in the pit- graves age], In OMERO tremila

anni dopo, Atti del Congresso di Genova (July 6-8th, 2000),

edited by F. Montanari with the help of P. Ascheri, Roma 2002,

561-578.

2. A. Greco, "La Grecia tra il Bronzo Medio e il Bronzo

Tardo: l'armamento di Aiace e il duo guerriero" [Greece

between East and West: Ajax’ weaponry and the Warrior

Duo] in "Tra Oriente e Occidente", studies in honour

of E. Di Filippo Balestrazzi, Padova 2006, 265-289.

3. A. Greco - M. Cultraro "When Tradition Goes Arm

in Arm with Innovation: Some Reflections on the Mycenaean Warfare",

in ARMS AND ARMOUR THROUGH THE AGES (from the Bronze Age to

Late Antiquity), ANODOS, Studies of the Ancient World, 4-5,

2004-2005 (2007), pp. 45-60.

4. A. Greco, "La Tomba di Aiace" [Ajax’

Grave] in "Eroi eroismi eroizzazioni", Atti del convegno

di Padova (Sept. 18-19th 2006), S.A.R.G.O.N. 2007, 102-112.

5. Hiller S., Scenes of warfare and combat in the art of

Aegean Late Bronze Age. Reflections on typology and development,

In Polemos, Le contexte guerrier en Egee a l'age du bronze,

Actes de la 7° Rencontre

Egeenne int. Univ. Liege, AEGAEUM 19, 1999, 319-330.

6. J. Bennet, Homer and the Bronze Age, In: A new companion

to Homer, I.MORRIS-B. POWELL eds, Leiden-New York Koln, 1997,

511-534.

7. Morris, Homer and the Iron Age, In A new companion

to Homer, I.MORRIS-B. POWELL eds, Leiden-New York Koln, 1997,

pp. 535 e ss.

8. A. Greco, 2006: Aiace, eroe frainteso. [Ajax, a

misunderstood hero] In: Eroi, eroismi, eroizzazioni dalla grecia

antica a Padova e Venezia – Atti del Convegno internazionale

di Padova, Sept. 18-19th 2006: 101-112

I'm also adding a text that I found on the web:

M.P.Nappi, 2002: Note sull’uso di "Ajante"

nell’Iliade, [Remarks on the usage of "Ajante"

in the Iliad] Rivista di cultura classica e medievale, Anno

XIV, N.2

A remark about Dolasilla’s weapons

Alessandro Manfroi proposes that Dolasilla’s

“magic” or “silver” bow may indeed be

a composite bow, imported from Asia by the “dwarfs”

and ended up by chance in the Fanes archer’s hands. This

suggestion, that might well explain the peculiar qualities of

the bow, is neither illogic nor absurd, although a little improbable

and maybe not really necessary. Alessandro also underlines that

the heroine’s arrows, if provided with metal heads, must

have been not only more penetrating, but also, just for having

shifted the baricenter forward, longer-ranged and more accurate.

|

|